Two and a half uses for student addresses

Student addresses are an interesting, and largely untapped, data point. They’re mostly seen as something that a school district's transportation department needs for creating bus routes...and that’s pretty much it. But there are a handful of cases I can think of where addresses provide us with an additional, useful piece of student data that nothing else really approximates.

First, let’s think about some generic models in which where a student lives might be useful for us, as educators, to know. There are, in my mind, two (and a half) such cases:

- When we suspect that where a student lives causes something;

- When where a student lives modulates how we intervene; and

- When where a student lives can serve as a proxy for something we care more about.

This last case – address as proxy for another variable – is the one I consider a half-case, largely because it feels like more of an academic topic than a practical one.

But let’s explore each of these.

Case 1: Address Causing Something

It feels pretty uncontroversial to say that where someone lives influences the choices they make. When I was younger and cooler and didn’t have kids, my wife and I lived in the Church Hill neighborhood of Richmond, VA. We are now less young and less cool and we have kids, and we live in a suburb about 30 minutes out of the city. We rarely go into the city anymore…because it’s 30 minutes away. Instead, we pick up dinner or coffee or whatever from places that are mostly not quite as cool but are also much closer.

In other words, where we live constrains our decisions.

This feels painfully obvious, but I’d argue it’s not something we often think about in education because students (and their families) mostly don’t choose what school(s) they attend – they’re simply zoned to go to a certain school based on their address, and that’s typically where they go.

Except there are cases where students do choose. Students might have options to attend specialty programs, center-based gifted programs, magnet schools, charter schools, etc, etc. And in these cases, where a student lives almost certainly influences whether they’ll choose to enroll in a certain program.

Imagine you’re an administrator at a specialty math/science center in your school district. Your program’s raison d’etre is to offer advanced, rigorous math/science classes to interested students from across the entire district. So you might want to know if you’re meeting this goal. In part, you might audit your classes to ensure they’re actually rigorous. You might look at test scores to ensure your students are meeting your expectations re: achievement. And you might look at college acceptances to better understand if your program is adequately preparing students for a future in math or science.

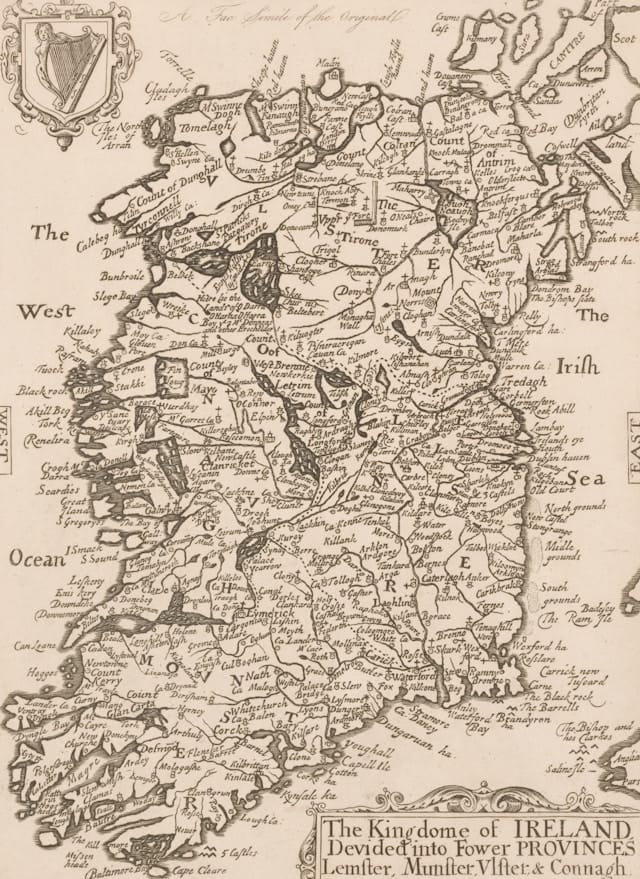

These are all reasonable approaches, but none of them can address whether your program is accessible to students throughout the district. To understand that, you need to examine where students live in relation to where your school is. If you’re in a geographically large district – in terms of square miles – but all of your students live within 5 miles of your school, then it’s hard to say you’re really meeting the needs of the students who might be interested in the program but don’t want to commute 40+ minutes to school each way.

And a pretty straightforward map could show you this.

Case 2: Address Modulates Intervention

The second general category of case where student addresses could be useful data points is if they modulate some intervention you want to deliver.

Imagine you’re a school social worker, and a considerable portion of your job involves encouraging students to attend school. So you interact with students – and families of students – who often miss school. Student addresses might be valuable data points for you not necessarily because you think where a student lives affects whether they attend school (although it’s possible that it does), but rather because it can inform how you support these students/families.

For instance, if you map out the home addresses all of your chronically-absent students, you might notice, hey, these 15 kids all live in the same neighborhood – it might be efficient for me to do some home visits. So you might conduct a home visit for these students earlier than you typically would because it feels efficient, based on this map you’ve created.

Case 2.5: Address as a Proxy

Like I mentioned earlier, this feels like more of an academic case than a practical one, but we might also think that where a student lives is useful because it serves as a proxy for something else we care (more) about. The proxy variable that immediately comes to mind is student socioeconomic status (SES). Student SES – or whether they receive free/reduced price lunch (FRL), which is itself a proxy for SES – is highly sensitive data, protected better than the Sorcerer's Stone in Harry Potter 1, and generally not something that school-district folks are granted access to use, even for well-intentioned research, without clearing lots of administrative hurdles (for what it’s worth, I agree with this restrictive approach).

But! Address data is not considered nearly as sensitive. And if you know a person’s address, you can get their Census tract from the US Census Bureau, which you can use to make inferences about poverty, income, etc using freely-available Census Bureau data.

In most boots-on-the-ground, I-want-to-use-this-data-to-help-my-students cases, this probably isn’t something anyone outside of academia or a heavy research role is much concerned with, though.

Processing Addresses with Free Tools

If you do want to work more with addresses, there are lots of free tools you can use. A quick and fairly painless way to get started is by using the US Census Bureau’s free geocoder service, which can take a .csv file full of addresses and give you the latitude and longitude for each address. You can then take these and plot them in tools like Looker Studio. Or, if you’re so inclined, you can use programming languages like R, Python, Julia, or Javascript (or many others) to code up your own plots.

Altogether, I’m under no illusion that student address data is in any way, like, some silver bullet that we can use to solve all of our problems. But I do think, in certain instances, it can provide a very useful data point.